Big picture, there are two different types of chords you’ll run into when learning guitar — which are major and minor. There are other flavors to chords we’ll get to in future lessons: 7th chords, sus chords, power chords, etc. But zooming out to the highest level, I think it’s most helpful to start with major vs. minor.

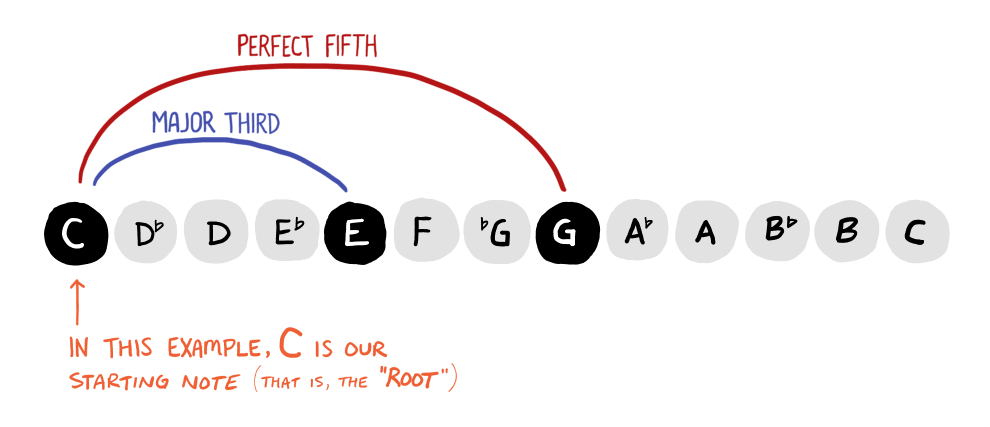

Major chords sound happier and more triumphant. They are constructed from any starting note (the “root”), from which a major third and perfect fifth are added. You may see this written in shorthand as 1-3-5.

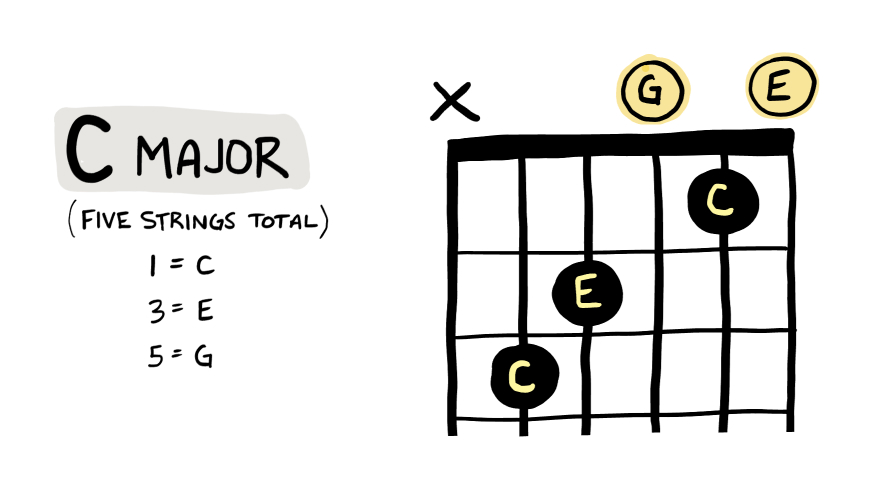

For example, if we start on the note C we can figure out the three notes used in a C major triad:

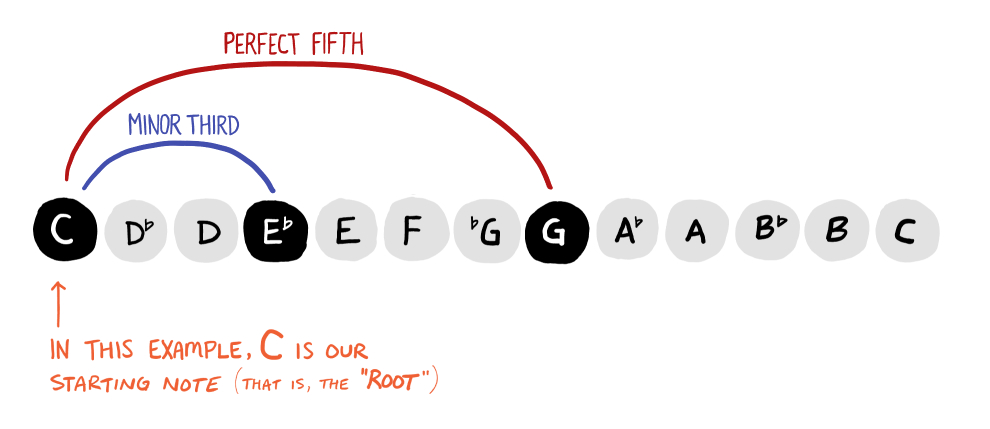

Minor chords sound sad and a bit serious or sorrowful. They are constructed from any starting note (the “root”), from which a minor third and perfect fifth are added. You may see this written in shorthand as 1-b3-5. For example, if we start on the note C we can figure out the three notes used in a C minor triad:

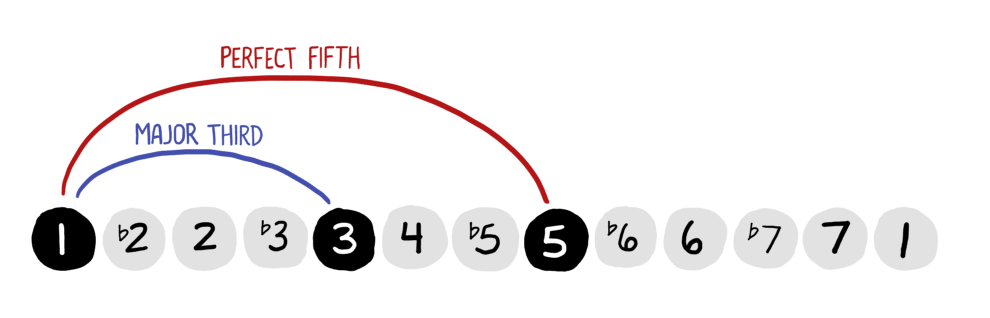

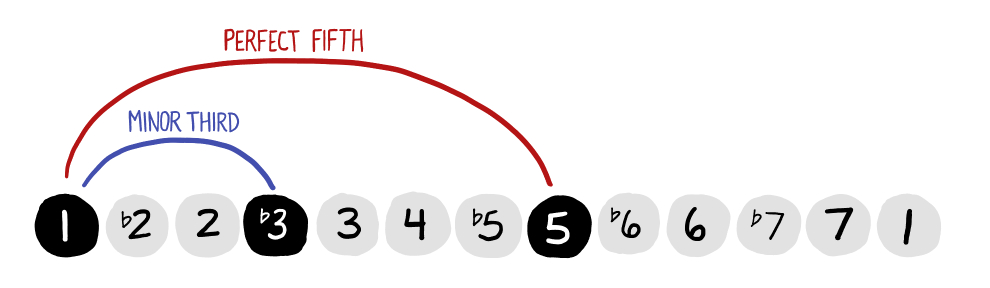

No matter which note you start with, constructing either of the triads shown above will always create a major (or minor) chord. Here’s the same diagrams, but each note is labeled with generic scale degrees (instead of the notes in the C major scale).

Major chord (1-3-5):

Minor chord (1-b3-5):

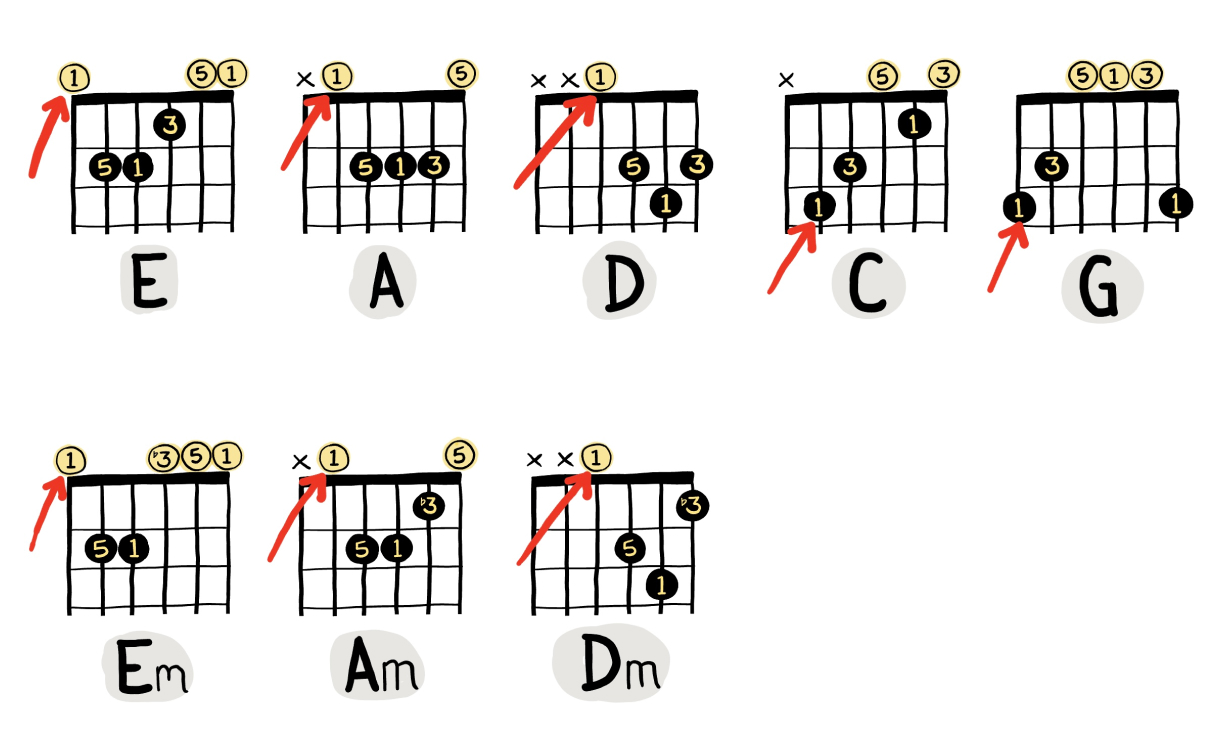

The major and minor triads are built with three notes. But why do some guitar chords use 4, 5, or 6 strings? What’s the deal with these extra notes?

Look again — you’ll notice that all these notes are ones, threes, and fives — and it’s okay if some of the notes repeat.

For example, the C major chord is built with the notes C-E-G. When playing a C major chord in open position, notice how it has two “C” notes, two “E” notes, and one “G”:

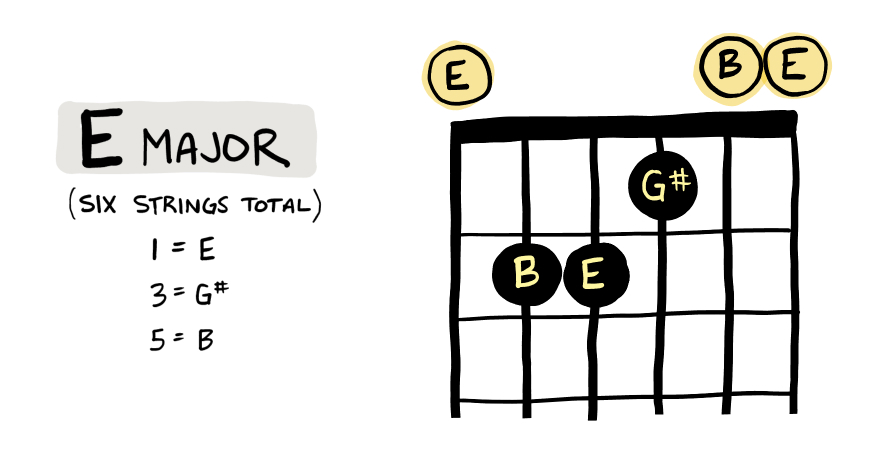

Conversely, the E major chord (built with E-G#-B) has three “E” notes, one “G#” note, and two “B” notes:

It doesn’t matter how many strings a chord uses… as long as it has at least one each of 1-3-5 (or 1-b3-5 for minor), it’s a valid chord!

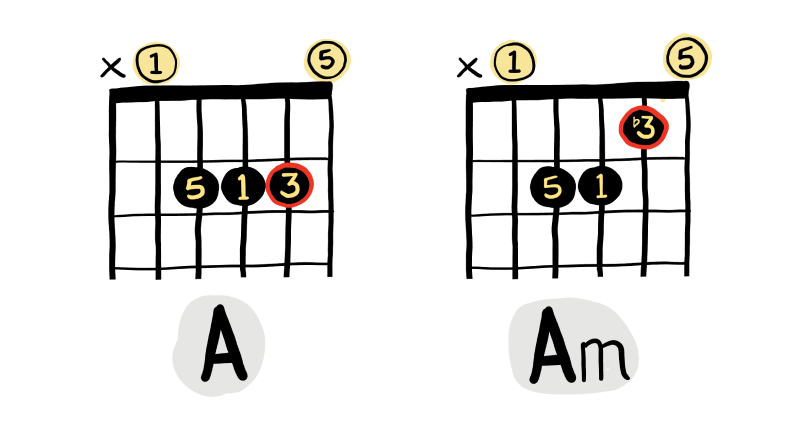

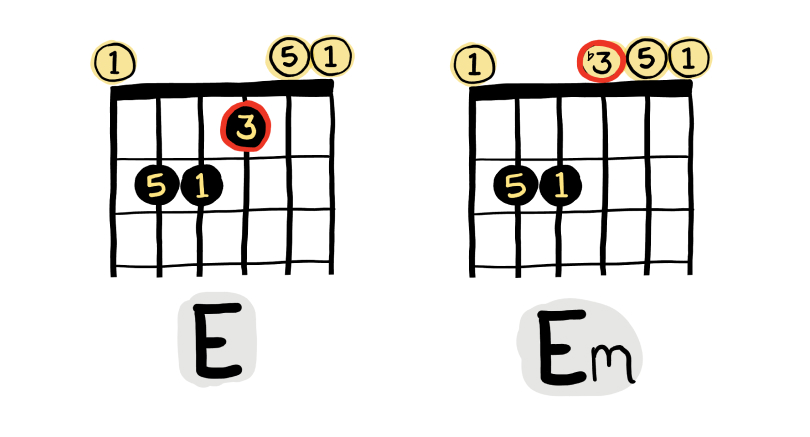

Notice how much these two types of chords have in common. The root note and perfect fifth are the same. It’s the “third” that is different between the two chord types: major third vs. minor third.

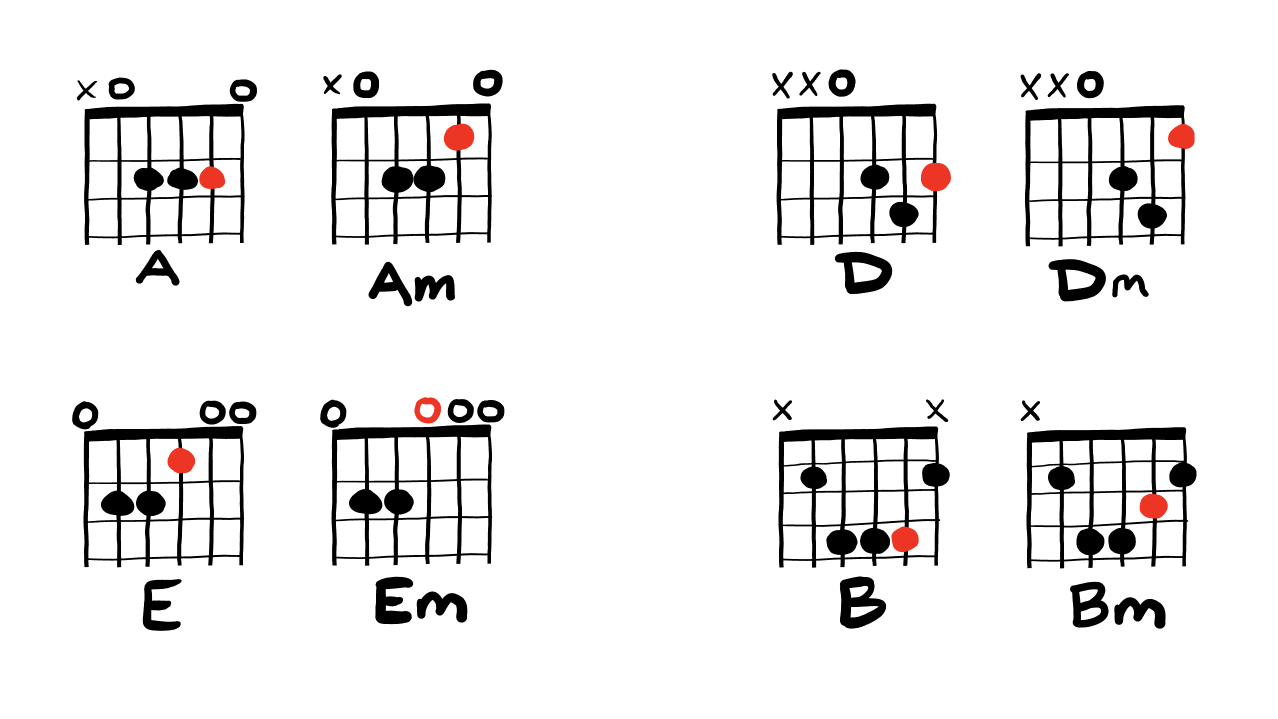

To illustrate this point, look at the following chord shapes. Notice how the major vs. minor version of each chord is different by only one note:

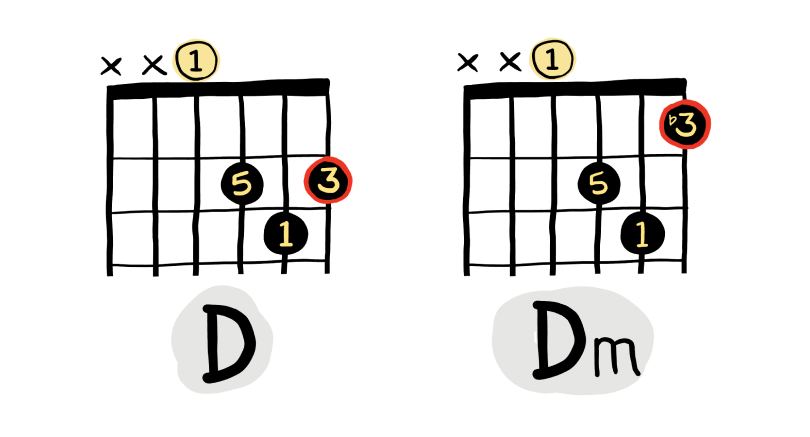

This “different” note is the major third (in major chords) and minor third (in minor chords). Here’s the same chord forms, but labeled with 1-3-5 and 1-b3-5:

As you learn chord shapes, pay attention to this specific note — it’s an incredibly helpful clue to identifying “the third” (major or minor) in any chord you’re playing.

One final point on this topic — unless specified otherwise, the “bottom” or bass-most note in any chord should always be the root note (or “1”). Look here at all the open chords, and notice how the thickest string in each chord is using the “1” note from the 1-3-5:

In the future, we’ll learn about exceptions to this (inverted chords, slash chords, etc) — but for now, it’s helpful to understand this convention.