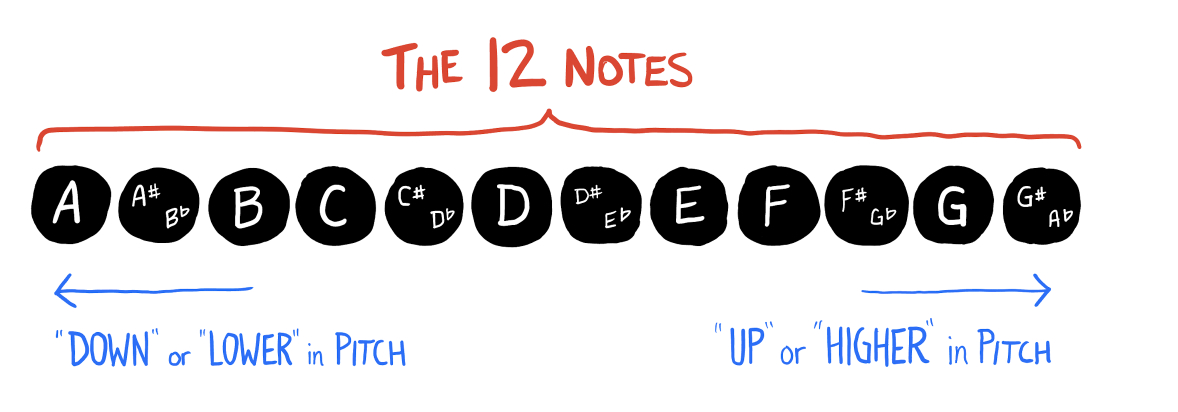

In Western music, the musical tones that are played (on an instrument) or sung (with a voice) are given a name. Written in a line, the order of the 12 notes looks like this:

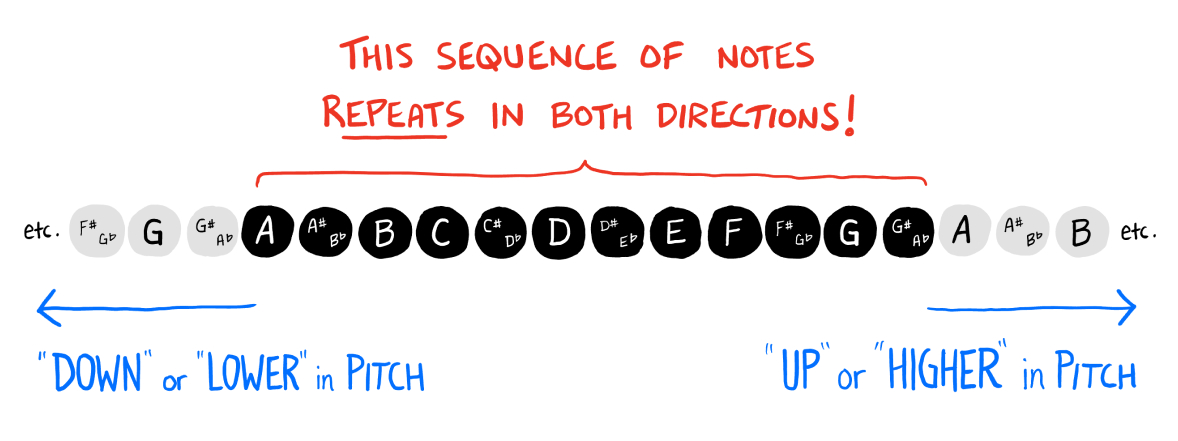

And importantly, when we reach the “end” of the 12 note sequence, you can keep going — and the cycle of notes repeats! This is true in both directions:

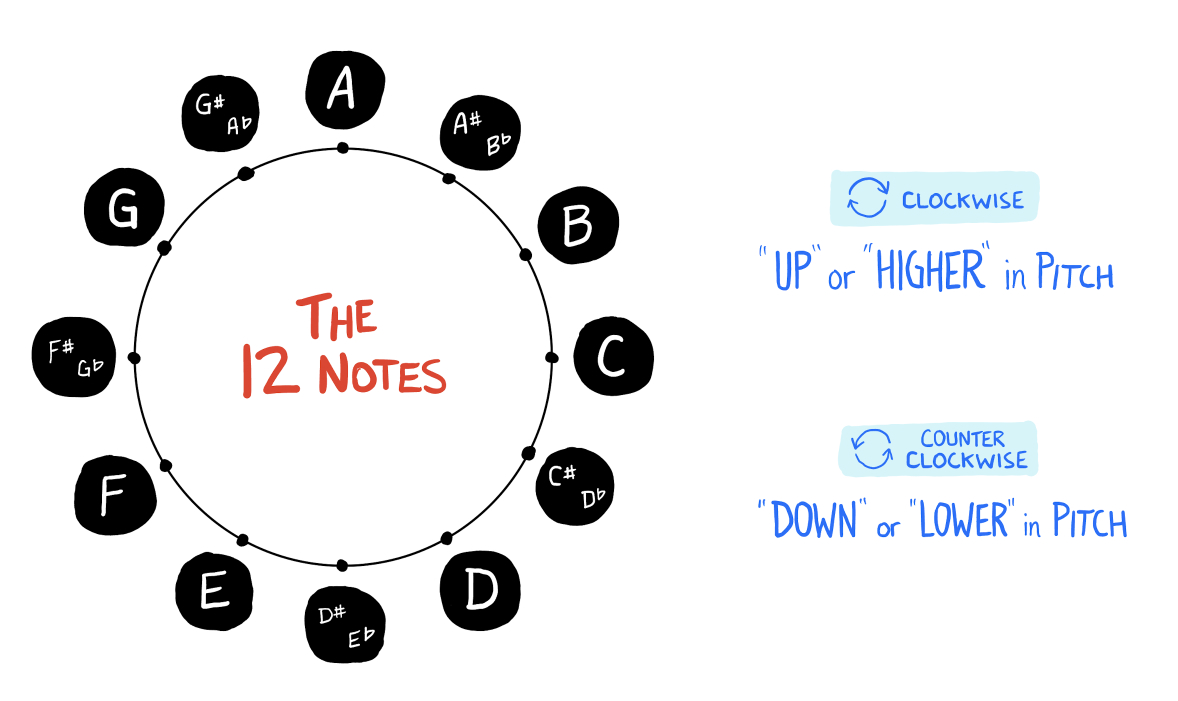

It may be more helpful to view the notes in this circular format. Similar to an analog clock, these notes “go around” in a cycle. That is, when you reach the end, you start again from the beginning (e.g. if you go up in pitch one note from G#, you arrive on A).

The 12 notes use the first seven alphabet letters (A-G). Some of the notes include sharps (#) and flats (♭) as part of their name.

Notes with sharps & flats can go by two different names. For example, the note between C and D can be called either C-sharp or D-flat — both of these names are valid, and they refer to the same note. In future lessons, when we get to the major scale, we’ll learn about when to use sharps vs. flats (but don’t sweat that now).

Spoken out loud, the 12 notes are as follows (starting in alphabetical order):

Notice how there are no notes with sharps or flats found between B & C, and likewise for E & F. This may seem like a weird quirk when first learning things, but it’s one of those things you’ll simply need to remember.

Here’s a handful of important concepts that I think are committing to memory. Getting a grasp on these will make everything that follows (on your music theory journey) a bit easier to understand.

The notes go “up” and “down” - In music, the notes are tied to the concept of pitch. Rather than saying “forward” and “backwards”, we’ll use the terms up and down. “Up” means higher in pitch (like a singing chipmunk), and “down” means lower in pitch (like a ship’s horn).

The notes repeat — The sequence of notes repeats, in both directions (up and down), like numbers on a clock. There’s no first or last note. When we reach the end, the cycle simply repeats itself and starts again. This means there are multiple “pitches” where you can play any note on the guitar (or, sing a note with your voice) — e.g. the open 6th string is a “low” E, and the open 1st string makes a “high” E.

The order of notes is fixed — the specific order of the notes is set in stone. For example, if you go one note higher in pitch from C, you will always arrive at C#. Again, this is similar to the hours on a clock (e.g. 5 o’clock is always one hour after 4 o’clock).

All notes are created equal - importantly, no note is special or stands above any of the others. We can construct any scale, chord, or musical key using any note as our starting point. Specifically, the note A is not in any way unique because it’s named after the first letter in the alphabet. Similarly, G isn’t inferior because it’s the final letter in the musical alphabet. Likewise, notes with sharps & flats aren’t in any way better or worse than their counterparts.

Similarly, here’s a few terms you’ll hear over-and-over when learning music or playing along with others. I suggest memorizing these as well:

Pitch - How “high” or “low” a note’s sound is

Sharp (#) - Higher in pitch by one note (ex: A to A#)

Flat (♭) - Lower in pitch by one note (ex: A to A♭)

Octave - Higher or lower in pitch by 12 notes (ex: A up to the next A)

The following are common terms for referring to neighboring notes — that is, one or two notes away from any starting point. You’ll notice these are two different ways of referring to the same thing (semitone & tone vs. half step and whole step)… I think it’s good to be aware of both. These are to essential to understanding for the next lesson, when we start looking at the major scale.

Half Step - Higher or lower in pitch by 1 note (ex: G to G#)

Whole Step - Higher or lower in pitch by 2 notes (ex: G to A)

Semitone - Higher or lower in pitch by 1 note (ex: G to G#)

Tone - Higher or lower in pitch by 2 notes (ex: G to A)

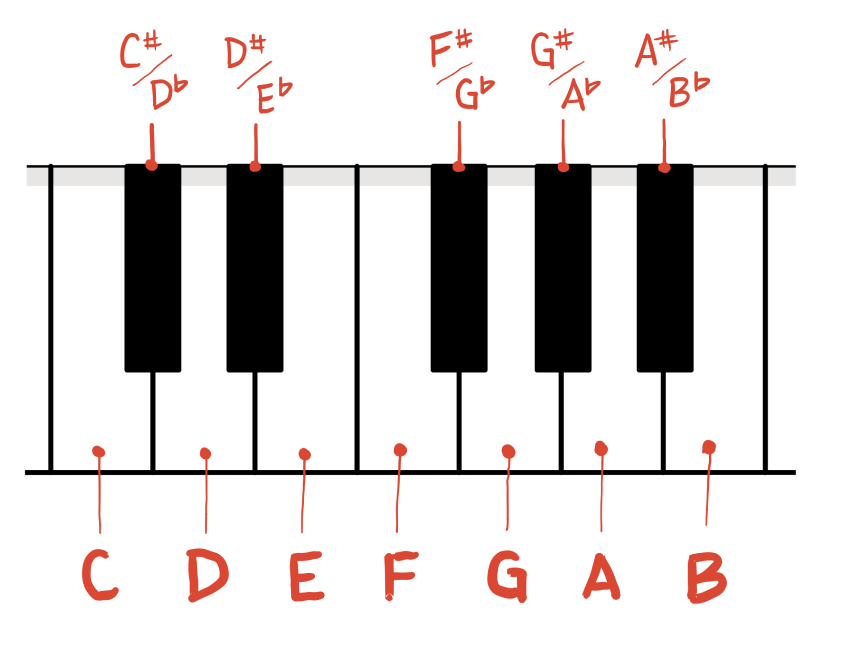

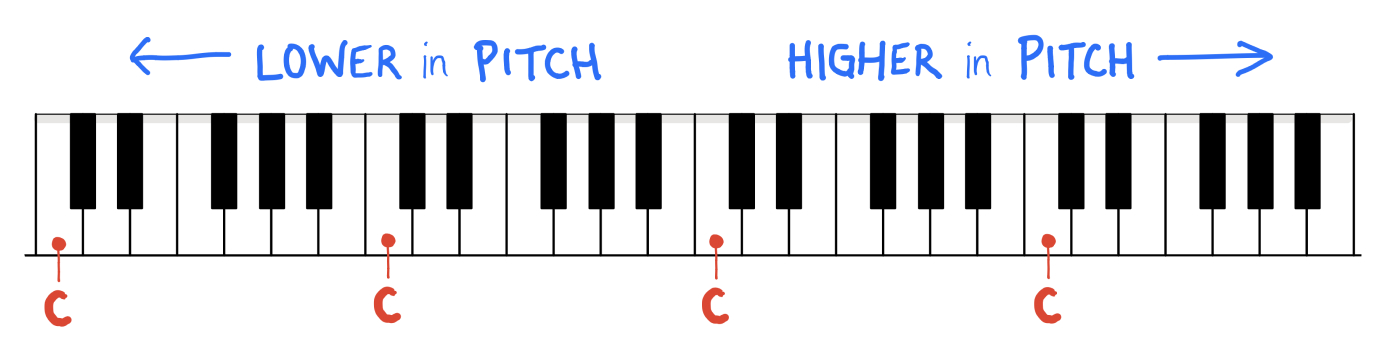

When learning the names of each note, a piano’s black & white keys make it amazingly helpful. All white keys are the letters A-G, while the black keys are used exclusively for sharps & flats. The 12 notes appear as follows. Note, C is typically the arbitrary “starting note” when first learning piano note names — hence me using it to start the sequence here.

When you look at the entirely of a keyboard, it’s easy to observe how the pattern of notes repeats. This is a good way to get a handle on the concept of an octave — that is, the distance from one note up (or down) to it’s next occurrence. If someone ever says “go up an octave” with a note or melody, they mean play those same notes, but one next octave up (in pitch).

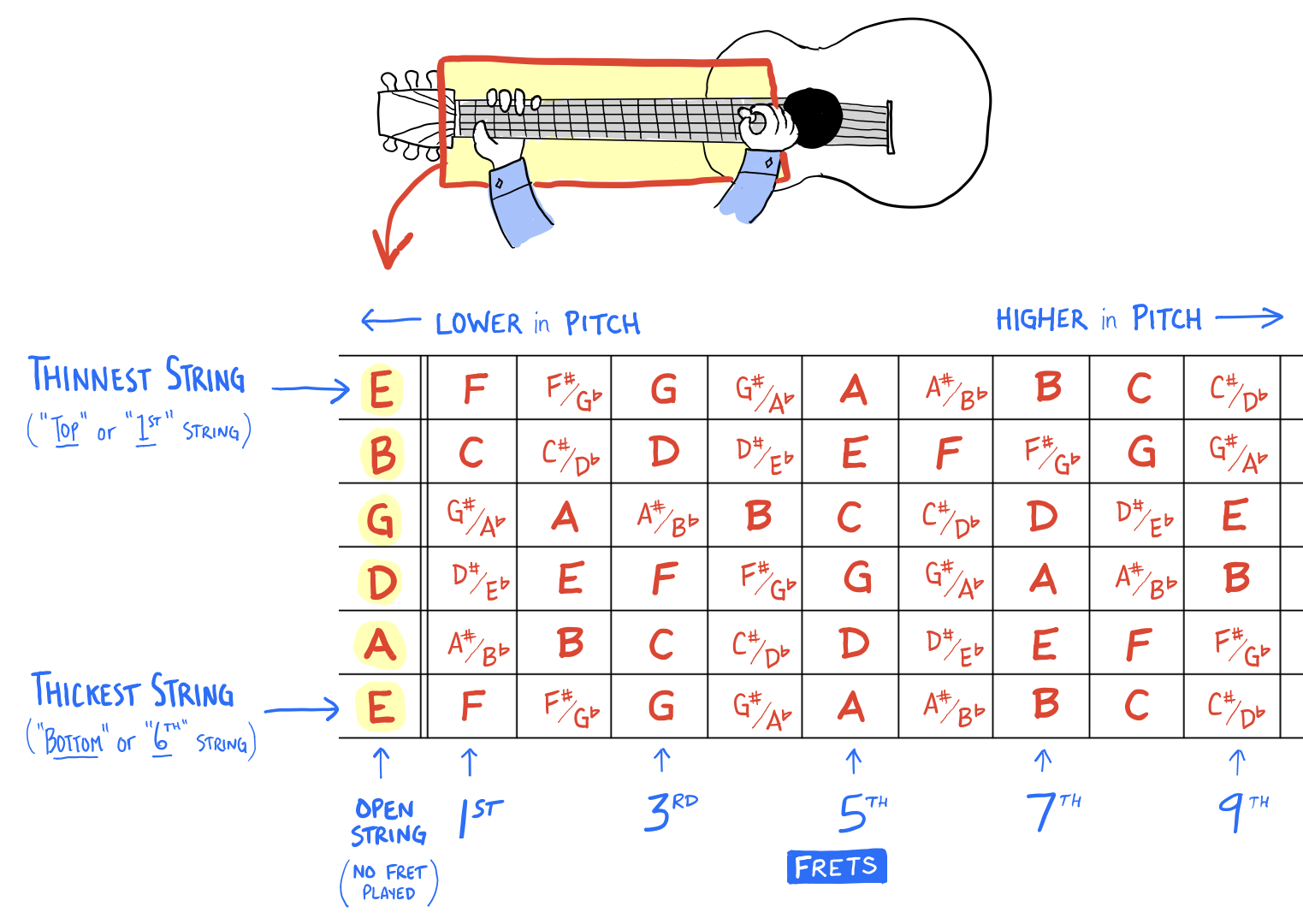

On a guitar, it’s a bit less visually intuitive to “see” the notes (compared to a piano). But just the same, here’s a mapping of things up through the 9th fret. For a print-friendly version of this image, get my instructional PDF cheat sheet — linked at the top of this page!

You don’t need to memorize the previous image, in my opinion. Rather, start with memorizing the notes that each open string is tuned to (E-A-D-G-B-E, from thickest to thinnest). If you know these 6 string names, and likewise know the sequence of 12 notes — you can use logic to deduce any individual note.

Before wrapping up this lesson, here’s a few non-musical examples to help reinforce the idea of the repeating cycle of notes. That being: (1) an analog clock face, and (2) a color wheel. In both cases, note how you can “keep going around” in the set order, and things eventually repeat from the beginning.

With the clock in particular, I find it helpful comparison because of how often we do mental math when it comes to things like If it’s 11am now, what time will it be 3 hours from now? As simple as this may seem, this exact concept is used in music all the time — e.g. If this is a G, what note will I get if I move three notes “up” in pitch?

And of course — occasionally when doing this sort of calculation, we need to cross the G# → A chasm (just like you may need to cross the 12 → 1 chasm with a clock). Ideally, with the 12 notes, you’ll know them well enough to do this without hesitation.

Here’s a few ways you can practice your mastery of knowing the 12 notes. I honestly suggest you go through the process of trying these out! It’s easy to say “yeah, I pretty much understand this” after reading all this information — but it’s another thing to force your brain to recall all of this information on-demand. Here’s what I suggest:

List the 12 notes in a line or circle - get a piece of paper and pen/pencil, and write out the 12 notes. Initially, you might start with A, but it’s actually helpful to try this starting with any arbitrary note — and make your way through the full sequence.

Fill the 12 notes in an empty fretboard map - for guitar playing especially, it can be helpful to label each note on the guitar. Start with a single string (using that string’s “open” tuning as the starting point). As a helpful hint, remember that the 12th fret of each string matches the open tuning note of that same string. A helpful modifier that may be a bit less daunting: try this, but only map the first 5-7 frets of each string.

Try the “3 Notes Away” Quiz - in practical guitar playing, a common situation is moving from a specific starting note (e.g. 5th fret on the thickest string = A) and then moving up, or down, 3 notes. What note do you end up on? Being able to do this from any arbitrary starting point is incredibly helpful. I demonstrate it in my video lesson.

Practice Listing the Notes Backwards - even if you skip sharps & flats, it’s an incredibly helpful musical skill to be able to effortlessly move backwards through the musical alphabet. For example, pick any letter (from A-G) and move backwards until you get to that letter again. e.g. D-C-B-A-G-F-E-D. Remember, saying things out loud is a great way to really get a handle on this!