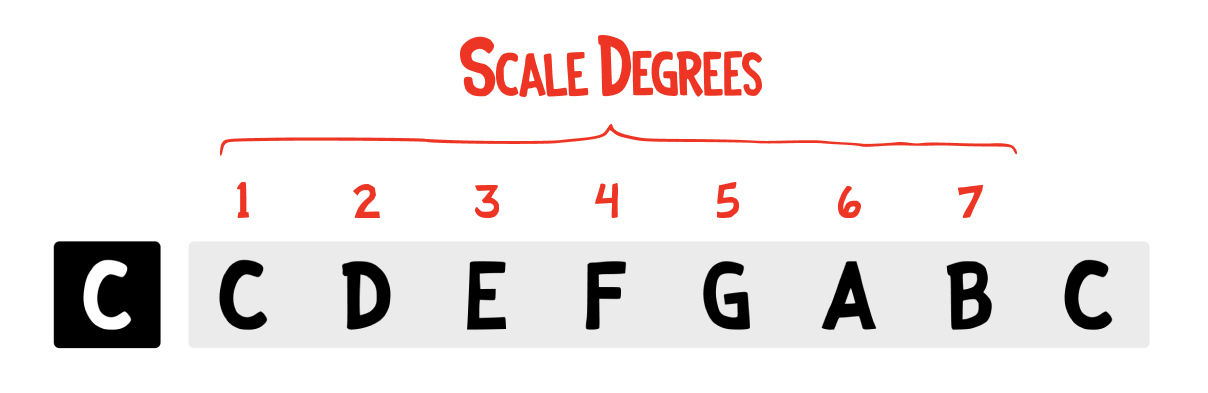

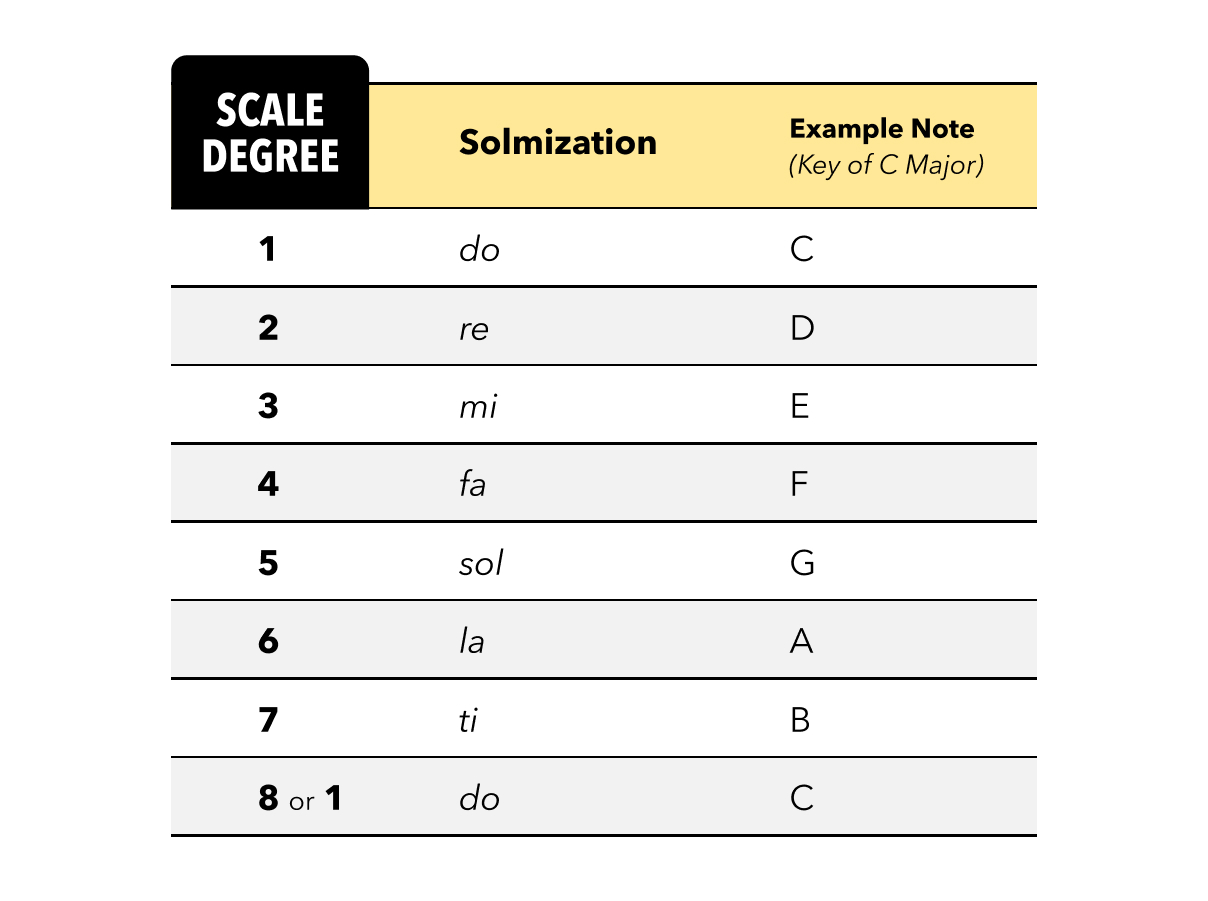

Quite simply, the term scale degrees refers to the number we give each note within a scale. There’s a few different ways to approach this, but the most helpful to start with us using the numbers 1-2-3-4-5-6-7 for the notes in major scale:

As the image above suggests, we’re simply applying these numbers to each of the ordered notes within the major scale. This allows us to refer to specific points in the scale using the scale degree of each note instead of the name of each note.

A real-world analog is giving someone directions to your home. You might say, it’s the third house on the left to someone who just arrived on your street… which is similar to using a scale degree. Alternatively, you could give your exact address — e.g. “125 Elm Street” — which is more akin to giving the precise note name. Similar to scale degree vs. note name, both get the job done — and it’ll often depend on context as to which you use when describing a note.

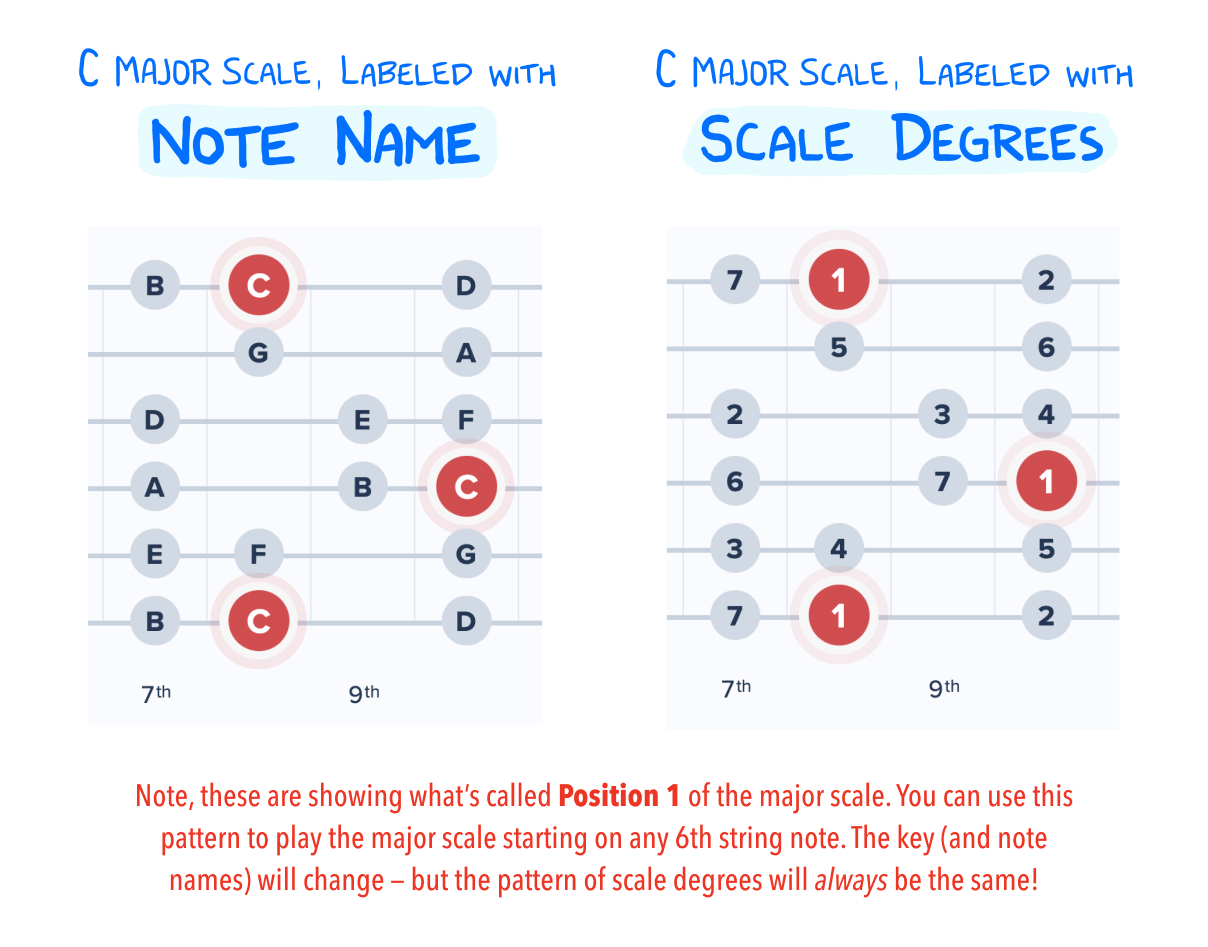

A very common way these are used is on fretboard diagrams. For example, here’s two octaves of the C major scale (showed between the 7th and 10th frets) labeled with note names and scale degrees. That is, two ways to show the same thing. Notice how the pattern of notes is the same — we’re simply changing the label:

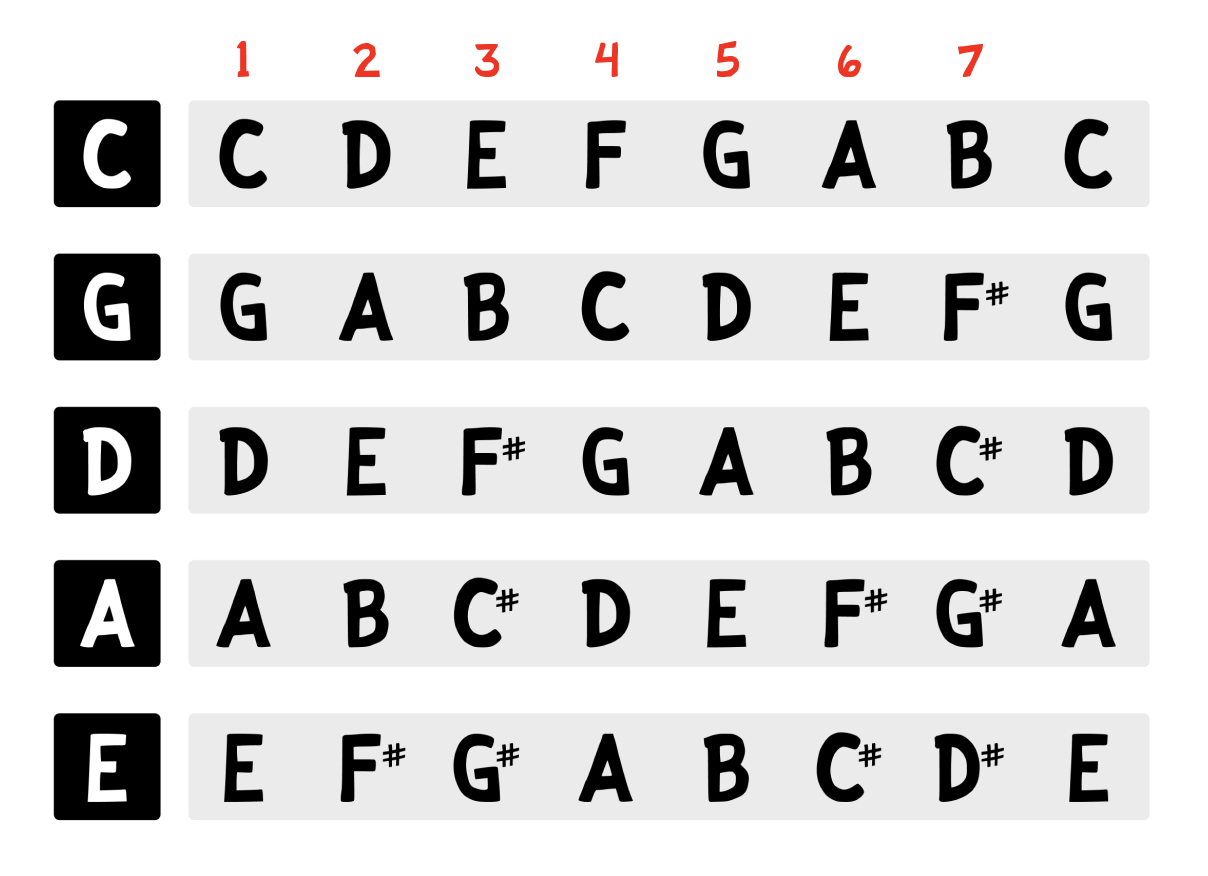

To be clear, scale degrees can be applied over any scale. For example, here’s the major scale for each of the 5 most common keys (on guitar), with the scale degrees shown on top:

Because in many cases it makes things far simpler.

Remember, the notes are different in each major scale — making it cumbersome to always rely on named notes when communicating musical information. In many cases, it’s easier to simply refer to numbered scale degrees to describe a melody/chord/scale/note — because no matter which major key we’re in, the scale degrees are consistent in their sound.

A few quick examples:

Describing an Individual Note - suppose a friend you’re jamming with, or your music teacher, tells you to play the “the 5” of whatever major scale you’re working with. You don’t need to know the note name of the 5th note in the scale… instead, you can just play the 5th note in the scale.

Describing a Melody - the first four notes of When the Saints Go Marching In is played using the scale degrees 1-3-4-5 (played one at a time). This maps to the lyrics “Oh when the Saints” that opens the song. If you’re able to play the major scale in any key, you can play this song using that four-note sequence.

Describing a Chord - given any major scale, you can play the major chord (based on the “1” note of that scale) using scale degrees 1-3-5. Similarly, you can play a major 7th chord using scale degrees 1-3-5-7. No matter which major scale we’re using, these chord formulas apply.

Describing a Scale - of the seven notes in the major scale, the major pentatonic scale can be played with notes 1-2-3-5-6. This is just one example of many possible scales you can play — and it’s a very common convention to write scale formulas using this scale degree shorthand.

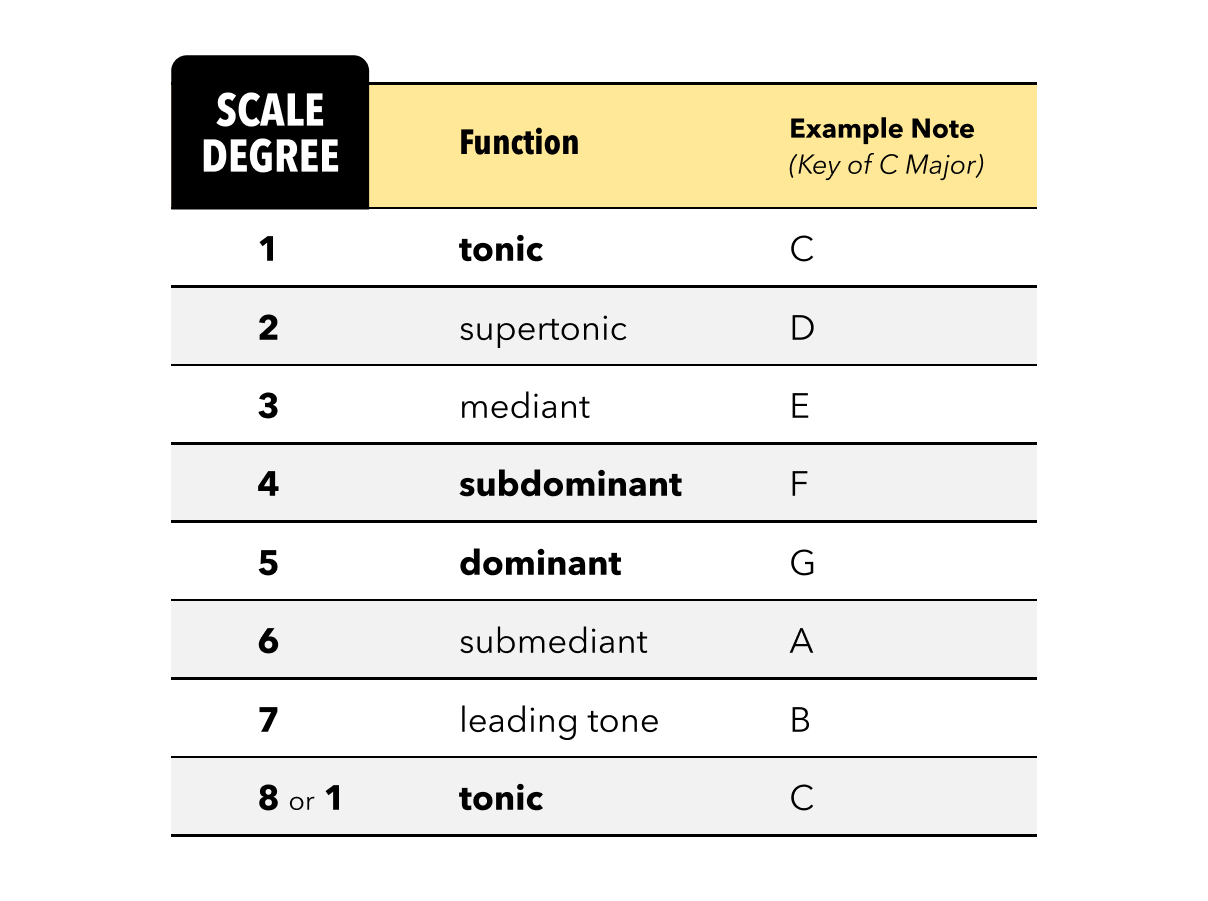

One convention it’s good to be aware of is the name or “function” of each scale degree. I wouldn’t consider this must-know for those of you just getting started with music theory — but it’s good to be aware that these terms exist:

Of the terms above, the ones worth remembering are written in bold. Specifically these two:

Tonic refers to the starting note of each scale, which will sound sturdy, stable, and like “home” within any scale context.

Dominant is a term you’ll hear come up quite often. It refers to the 5th degree of the major scale, and will return in future lessons (e.g. dominant 7th chords, secondary dominants, etc).

While we’re on this topic, a quick detour into solfege – which is a syllabic system for identifying the notes in the major scale. The obvious example here is the song “Do-Re-Mi” from The Sound of Music. In that song, Julie Andrews’ character teaches the Van Trapp children about the major scale using these spoken syllables:

Here’s the clip from the film. Give it a watch & listen, referencing the table above. Notice how she’s very frequently going “up” the major scale, singing exact note that matches each syllable name:

The second part of the song continues this trend, but gets a bit more advanced. Starting around 0:32, notice how she breaks away from always singing the notes in a linear, ascending order. Instead, after assigning each child one of the notes (and its matching syllable), she’s able to create a more advanced melody by instructing them to each sing in a prescribed order):

In my opinion, it isn’t necessary to memorize these. But, as you make your way into the realm of music theory — listening to the music & lyrics of that song (with these concepts in mind) might help these concepts cement themselves in your mind. Specifically, each note Julie Andrews sings matches that degree of the major scale.

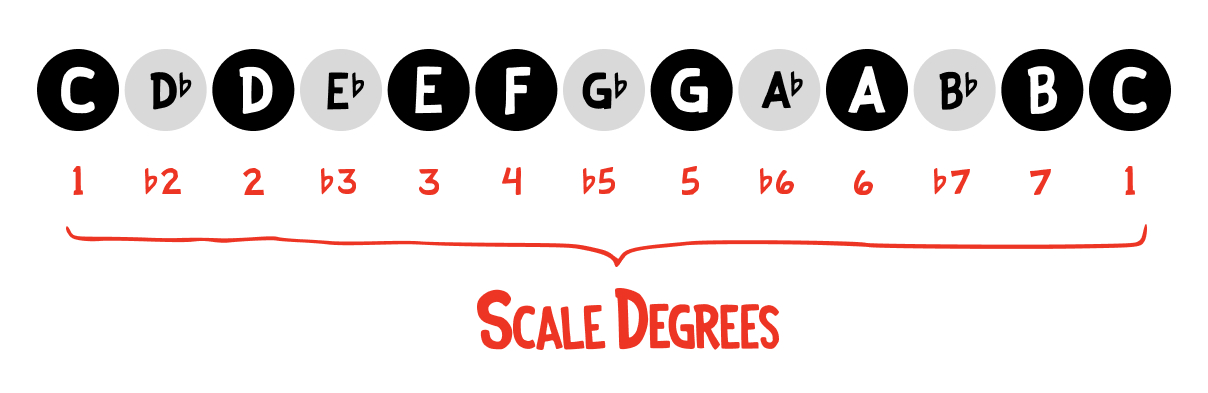

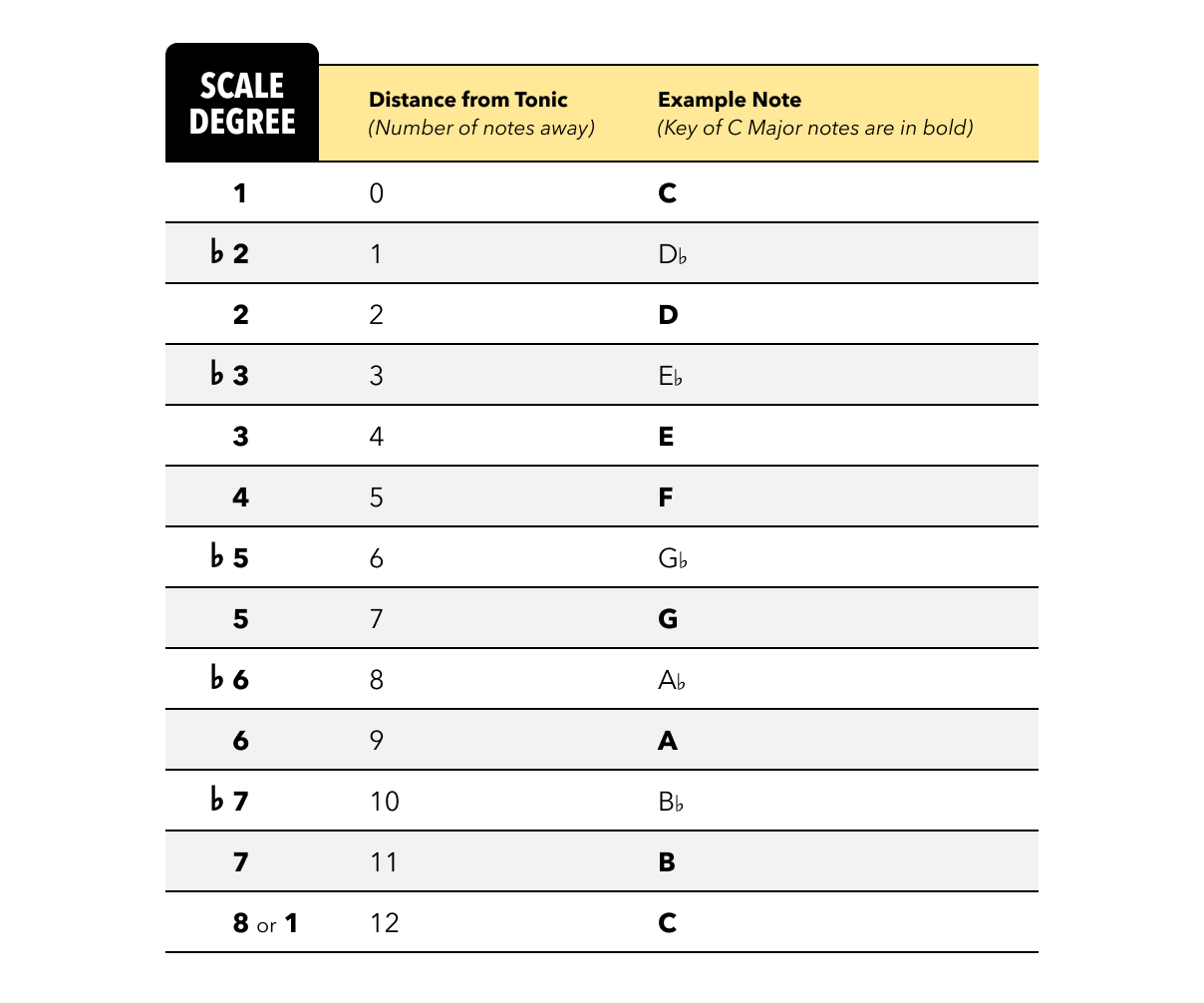

It’s important to understand that scale degrees aren’t inherently tied to the notes in the major scale. For example, what if a song makes use of a note that’s after the “two” but before the “three”? Fortunately, we can account for that as follows:

The same information, displayed in a vertical table, looks like this:

Armed with this knowledge, we’re able to describe things that weren’t possible before. For example, using the b3 (“flat three”) and b7 (“flat seven”) is very common, especially in the blues. Here’s a few other examples:

The minor pentatonic scale can be written using scale degrees 1-b3-5-6-b7

The major blues scale can be written using scale degrees 1-2-b3-3-5-6

The minor chord can be built using scale degrees 1-b3-5

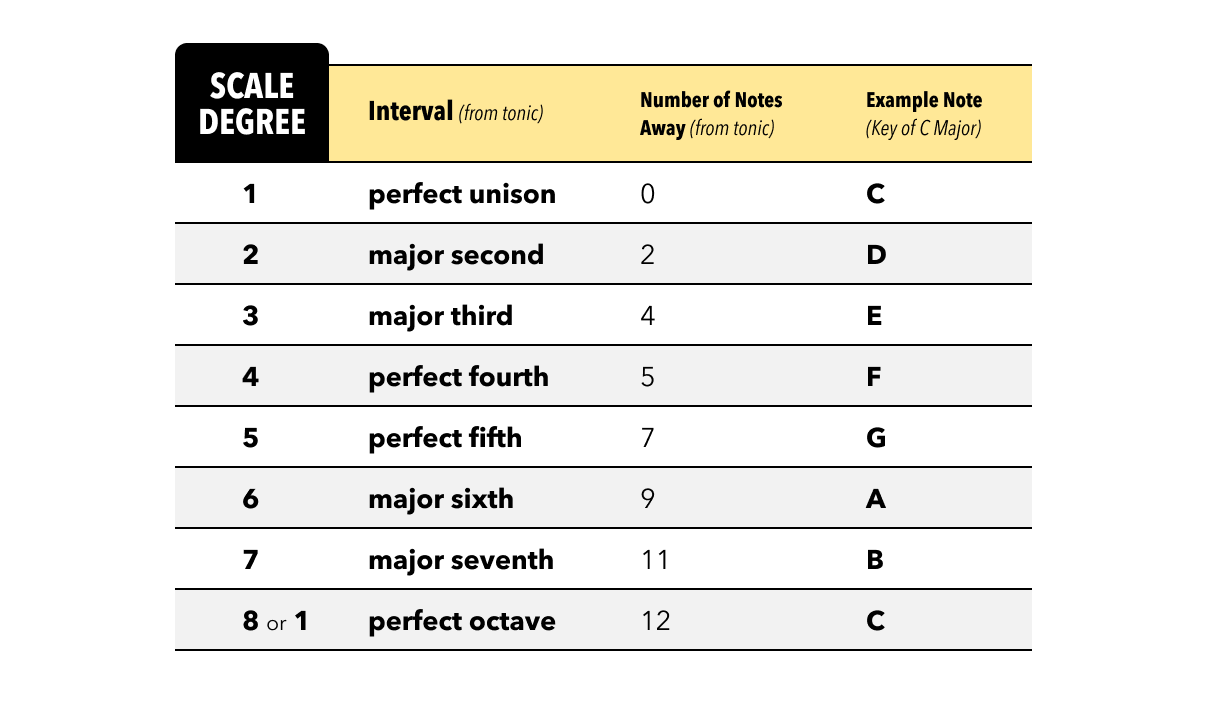

An interval is simply the distance between any two notes. It’s related to scale degrees, and in some cases can overlap quite a bit! But there are important differences, which I’ll explain.

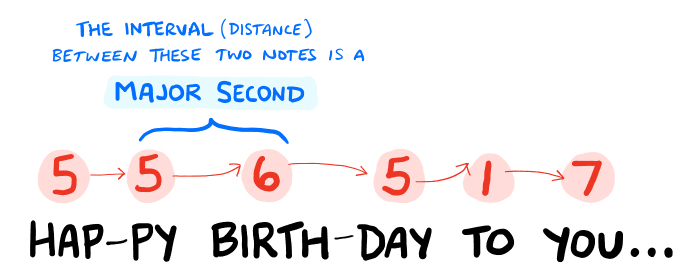

Here’s a table showing how scale degrees & intervals can be used to describe the same thing. That is, the distance between the tonic (i.e. the “1”) to any other note in the scale. Note how we’re introducing terms such as major and perfect. It’s okay to ignore these at first… and simply notice the intuitive similarities between scale degree and interval (e.g. the “2” maps to “major 2nd”).

However, intervals can also be used to describe notes that are not in the major scale. Here’s an expanded table to help visualize this. Notice the introduction of the term minor into the name of some intervals:

If this is new to you, don’t feel like you need to memorize this entire table. Rather, be aware these terms & concepts exist. Over time, you’ll notice some of these concepts emerge in future lessons — and that will help cement things in your brain.

For example, earlier I noted how the major 7th chord is built with scale degrees 1-3-5-7. With the table above, you can see how that 7th scale degree maps to the major 7th interval, as opposed to the minor 7th.

Again, recall that an interval is the distance between any two notes. In some cases, we’ll have two notes that are being compared without any established major scale context. Here, scale degrees are out the window.

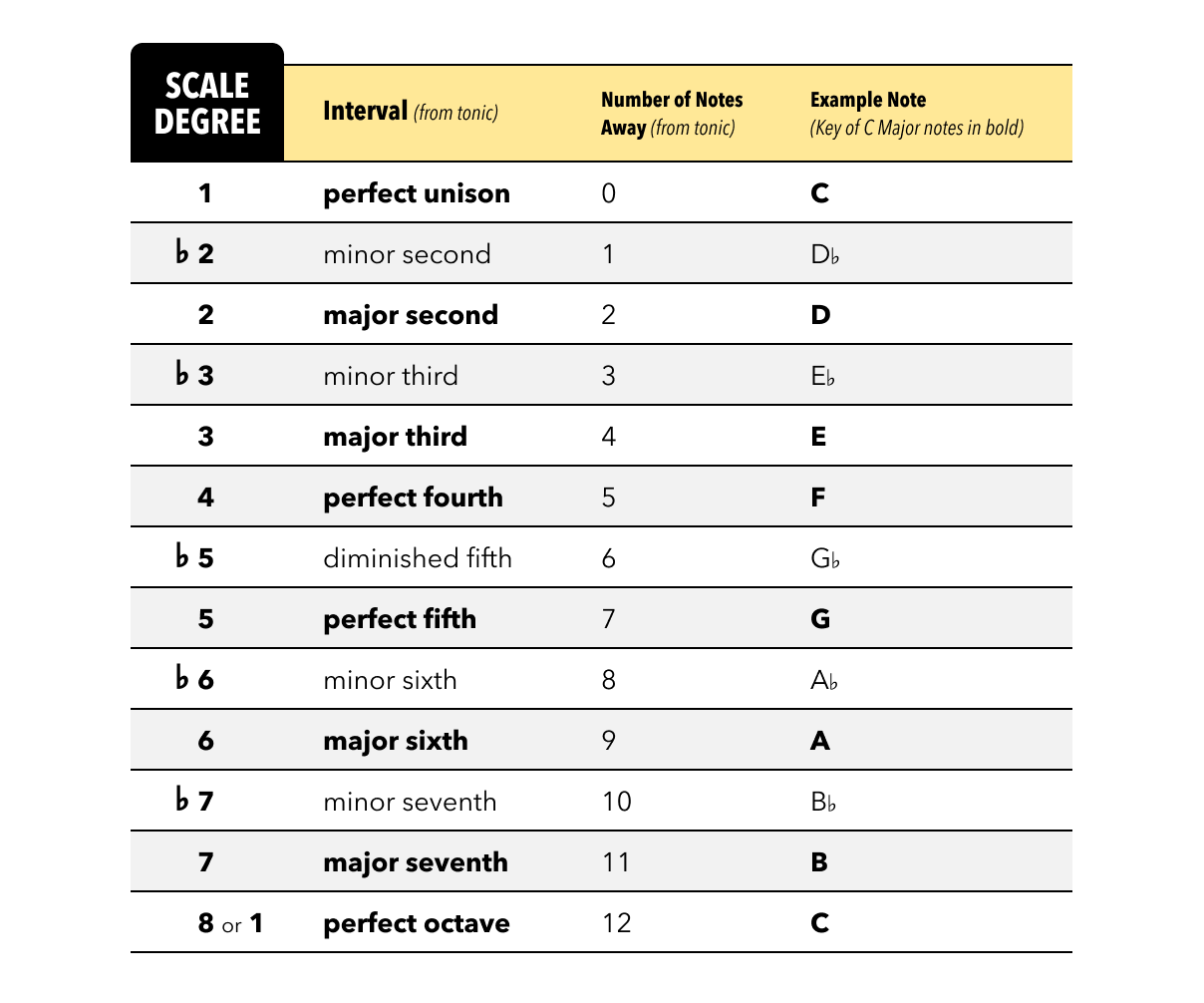

For example, let’s look at the opening phrase of Happy Birthday. If we look at the scale degrees used to create this melody, it’s as follows. Remember, for any major key following these scale degrees will create this recognizable song:

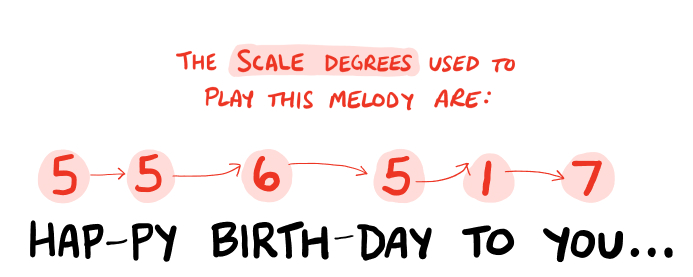

But, how would we describe the distance (interval) between the second and third syllables? In this example, the interval is entirely separate from the scale degrees. Specifically, it’s a major second — which is two notes away:

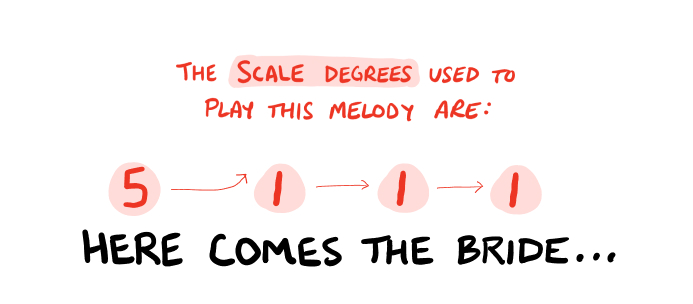

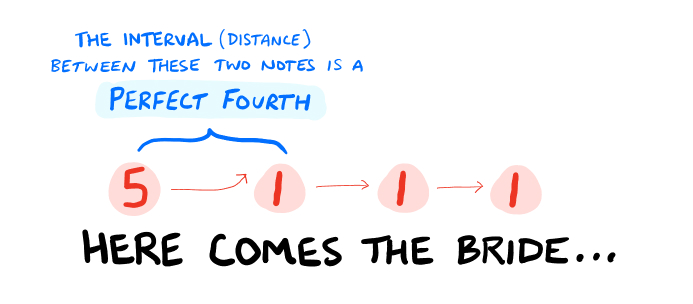

Another example is Here Comes the Bride, which is properly known as Wagner’s Bridal Chorus. In terms of scale degrees, the opening melody looks like this:

But again, if we measured the interval between the first two notes — it’s a perfect fourth — which is five notes away:

I share these examples simply to underline the important fact that these two concepts are related, but not 100% the same.

Intervals have an important role to play in future lessons, especially when we get into ear training & developing your ability to recognize the tones used in melodic phrases. But, all that is for another day!